I love solving small programming challenges. If you do too, I recommend exercism.io. One of the many challenges on this website is about transcribing DNA nucleotides to RNA nucleotides. I was able to solve this by using Elixir. I also found that I could apply metaprogramming to improve my answer. In this blog post, I will walk you through this process of improvement.

Basics

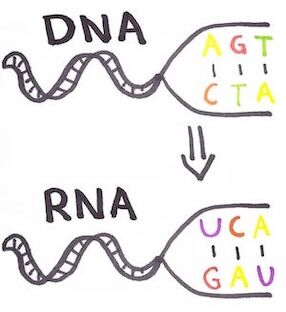

Before we can solve this challenge, we need to figure out the mapping between the nucleotides that make up a DNA strand and the corresponding representation in RNA. The mapping is A to U, G to C, T to A, and C to G. I've drawn out an example below:

Now let's implement this in Elixir! We can define multiple functions with the same name which are referred to as same head functions. In addition, we can use pattern matching on the argument to represent the mapping between the nucleotides. Doing so, we end up with the code below:

defmodule RNATranscription do

def to_rna("G"), do: "C"

def to_rna("C"), do: "G"

def to_rna("T"), do: "A"

def to_rna("A"), do: "U"

end

Following this, we can try out our module in the Elixir REPL called IEx and give it a valid DNA nucleotide. As can be seen below, this returns the correct corresponding RNA nucleotide:

iex> import_file("rna.ex")

iex> RNATranscription.to_rna("T")

"A"

Now we can use this module to take a DNA strand and split it into a list of DNA nucleotides. Each of these nucleotides is then mapped to its RNA equivalent and joined to produce the RNA strand. One way to do this is by using the REPL:

iex> strand = "GCAATTA"

iex> strand |> String.graphemes() |> Enum.map(&RNATranscription.to_rna/1) |> Enum.join()

"CGUUAAU"

This bit of code could be placed in a method called "decode" and we would be done! But now imagine the discovery of new RNA or DNA nucleotides. This would mean that additional letters would have to be added to our code. We could write a few new functions matching these new DNA nucleotides that will return the RNA ones. Though doable by hand, we could leverage the power of Elixir metaprogramming and define functions from a mapping so future extensions are easy. Let's have some fun!

Metaprogramming

Before we get into applying metaprogramming to our example, I want to go a bit more in-depth on the subject. One amazing thing about Elixir is that it is mostly written in.. Elixir! According to Github, at the time of writing this blog post, it contains about 90% Elixir code and only 9% Erlang code. Having a language written in the same language as the source code makes it easier to read and contribute to because you already know the language. Most of it is built using metaprogramming on top of a small core. An example of this is if/else. This is a simple macro for case. So the example code below...

if is_thruthy?() do

do_something()

else

do_something_else()

end

..gets compiled down in an intermitted step:

case is_thruthy?() do

x when x in [false, nil] ->

do_something_else()

_ ->

do_something()

end

You can read more about the source code in the Kernel library. This will show you how Elixir works beautifully. You can see the only falsely values are false and nil, everything else is truthy.

To get a sense of how we can implement something like this, let's try something out in the REPL. Using unquote we can take an expression and make it static on compile time. And with quote we can receive the AST from the block passed to check what we've created. The AST is what Elixir uses to represent our code before compiling down to Erlang. To see what the AST represents we use Macro.to_string/1.

iex> dna = "G"

iex> ast = quote do

...> unquote(dna)

...> end

iex> dna = "C"

iex> IO.puts Macro.to_string(ast)

"G"

As you can see in the code above, the unquote function returns the value "G" even if the value of dna is changed afterward. Through additional experimenting, we can find out if this can be used to set the value to match the argument in our same head pattern matching. We do this by writing the to_rna as we normally would but swapping out the argument and return value with the unquoted values of the DNA and RNA.

iex> dna = "G"

iex> rna = "C"

iex> ast = quote do

...> def to_rna(unquote(dna)), do: unquote(rna)

...> end

iex> IO.puts Macro.to_string(ast)

def(to_rna("G")) do

"C"

end

As you can see, the value "G" is set as the argument and "C" is set as the return value. This looks exactly like one of the functions we wrote by hand. But instead of writing it manually, we've used the value of dna to set the value on which the to_rna function needs to match and rna to set as the return value. Knowing this, we can bring everything together and create functions for our mapping. We can create the DNA to RNA mapping by creating a function for each key and value pair that matches on the DNA and returns the RNA. We'll use a simple for-comprehension for looping through our mapping:

defmodule RNATranscription do

mapping = %{ "G" => "C", "C" => "G", "T" => "A", "A" => "U" }

for { dna, rna } <- mapping do

def to_rna(unquote(dna)), do: unquote(rna)

end

end

After loading the file in the REPL, it gets compiled and all functions get defined:

iex> import_file("rna.ex")

iex> RNATranscription.to_rna("T")

"A"

And there you go, we've created compile-time functions! We could take the automation even further by hosting the mapping somewhere, using a hook to create an Elixir package when it changes, and publish it without the interference of a developer.

In conclusion

Elixir macros allow us to create awesome stuff. Though this awesomeness does come with a word of caution. It might be harder to understand what your code does and where some functions come from. New developers to your project with macros might have a hard time finding their way around. It is a tradeoff you have to make. Some might argue that using macros for a small mapping such as in our example above might be overkill. And I won't argue with that. However, it is fun to write and show you how you can define compile-time functions.

If you are interested in learning more about macros in Elixir I highly recommend the book Metaprogramming Elixir which goes deeper into the subject.

*[DNA]: DeoxyriboNucleic Acid *[RNA]: RiboNucleic Acid *[REPL]: Read-Evaluate-Print Loop *[IEx]: Interactive Elixir *[AST]: Abstract Syntax Tree